A New Delhi

01.2016 - 03.2016

Named capital of British India in 1911, but not inaugurated until 1931, New Delhi was at least the 8th city to be built on this stretch of the Yamuna, with the intention of placing the British Empire as the next (and final) in a series of imperial cities[1]. The vast spaces and imperial monuments of New Delhi would not only demonstrate, but exacerbate the overcrowding of its neighbor Shahjahanabad (or Old Delhi) to the north[2]. Although the geometry of the new city was in some respects intended to align with or accommodate certain important historical monuments in the area, its hexagonal planning and large green spaces takes much more from Sir Edwin Lutyens relationship to the Garden City Movement. In the end, the grandeur of New Delhi was to serve the British for but a few years, ultimately becoming the excessively monumental home of the new independent India in 1947.

1. Hunt, Tristram. Cities of Empire: The British Colonies and the Creation of the Urban World.

2. Legg, Stephen. Spaces of Colonialism: Delhi’s Urban Governmentalities.

Imperial Style – the Rashtrapati Bhavan

01.2016 - 03.2016

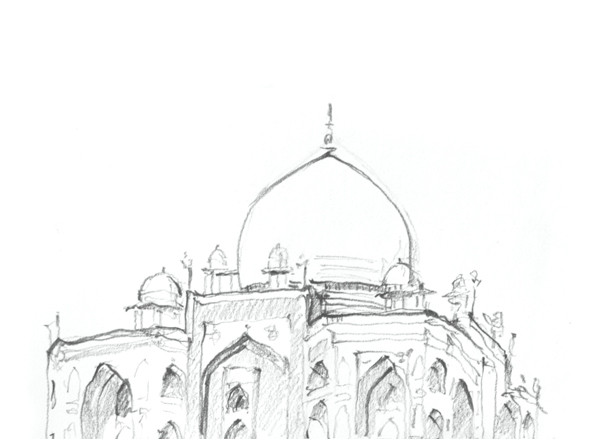

The Rashtrapati Bhavan, once the British Viceroy’s House, is now home to the President of India. It is positioned at the head of the Rajpath, the major East-West axis of the new city which faces India Gate on the East (and hints at a further connection the the Purana Quila fortress which is not quite in alignment.) Sir Edwin Lutyens, master planner of New Delhi, designed this building himself, attempting to create a new unified architecture for the British Empire of India taking elements from a variety of regions and religions. There is certainly a precedent for English architects attempting to mimic Indian architecture (see the Royal Pavilion at Brighton) but here Lutyens creates what may be a new style, albeit visually “Indian” to western eyes.

The form of the dome, the most distinctive feature, is said to be influenced by the Buddhist Sanchi stupa in Madhya Pradesh rather than the more local forms of Mughal domes. This reference can be seen in the dome’s geometry, apex, and decorative collar – which bears a motif that is used elsewhere in the capital, for example at the protective fence of the roundabouts near the Parliament building.

Decoratively the building has been somewhat reduced, which may be due to the trend in contemporary architecture towards an absence of ornament. The building is also set back from the main road by a vast lawn burrowed with driveways and hahas, making excessive ornamentation also superfluous and unnecessary. However, decoration is still to be seen, such as in what has come to be known as the “Delhi Order” of column capitals which Lutyens developed.

This translated and transformed style is seen in some mansions completed just prior by Lutyens for the Maharajas’ houses in the prime blocks around India Gate (eg Hyderabad and Baroda Houses) and was also appropriated by other architects (Jaipur house by Sir Arthur Bloomfield). The adoption of this royal New Delhi style associated with the Viceroy’s house rather than a representatively local style as embassies today do, could represent allegiance and cooperation with the empire, as well as an understanding of the benefits this relationship would provide. This could be seen as a strategy of creating a new hierarchical social order as a means of maintaining allegiances with local Maharajas. [1]

1. Hunt, Tristram. Cities of Empire: The British Colonies and the Creation of the Urban World.

Secretariat + Security

01.2016 - 03.2016

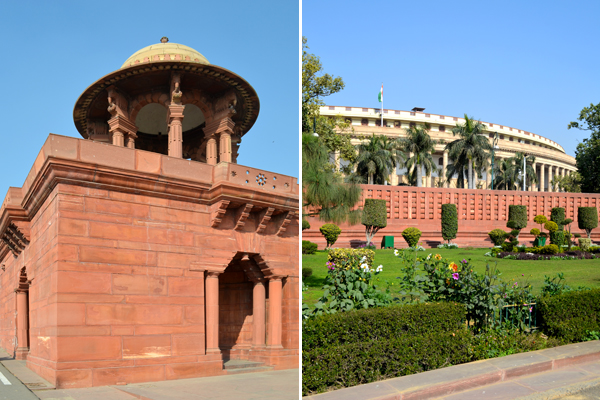

It has been asserted that Lutyens was dismayed by the massing of Sir Herbert Baker’s two Secretariat buildings flanking the Rajpath as it rose to the Rashtrapati Bhavan at the peak of Raisana Hill. The embankments forming a plinth at the east of the Secretariats do somewhat diminish the appearance of the dome of the house itself, but they do provide a larger visual impact for the government buildings as a whole, perhaps more in line with the more balanced government organization of today.

However, it is actually through these retaining walls that emerge from the topography of the Raisana that the Secretariats can maintain a sense of openness. Security was important in the 1920-30’s as the capital city was taking shape in parallel with a growing independence movement, communalism, and dissatisfaction with conditions in the old city to the north [1]. Towards the present day, security remains a concern with continued agitation from various castes, religions, and the growth of terrorism. As such, Baker’s siting provides security through mass and overlook without the extensive use, as elsewhere in New Delhi, of traffic barricades and fences. The Rashtrapati Bhavan in addition to a filigreed fence and movable barriers also provides security and visibility via a system of hahas/drives in its front lawn.

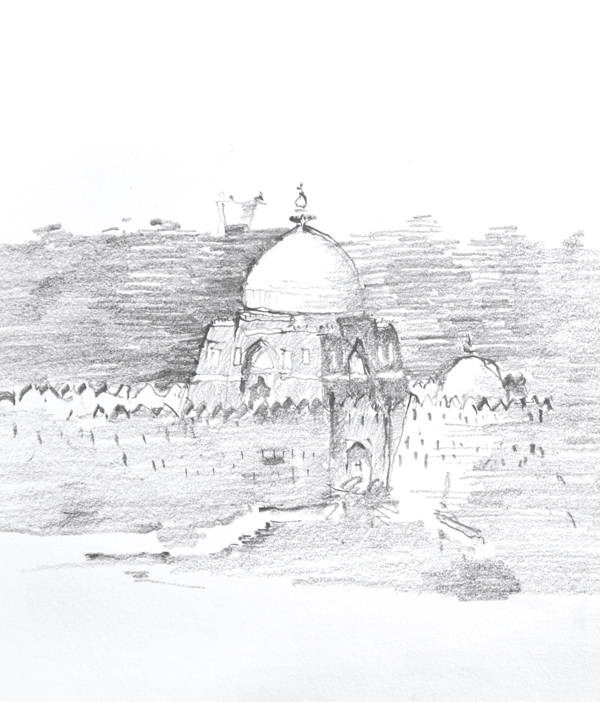

Throughout the historical cities of Delhi are distributed a number of tombs set within gardens and surrounded by walls. Instead of serving as mere barriers, an idea of an overall geometry defines the tomb as well as the garden and the wall. The walls complete a composition and are sometimes spatialized and partially occupiable. Humayun’s Tomb for example sits atop a plinth which protects, provides access, and is designed to maintain line of sight to the elegantly proportioned mausoleum and dome. The fort surrounding the town at Tuglakabad is the visual identity of the urbanization itself.

In contrast, today security is maintained through smaller apparatus/nodes. The fence with no individual character. The security booth as an appendage. Foliage above which masks any remaining view. A complex of magnetometers and frisking. And of course bureaucracy, official documents, functionaries and paperwork which can be the most impenetrable barrier.

Today security appears out of the domain of architecture, but in the traditional security measures of spatial manipulation visibility can be provided and the appearance of the city designed, rather than an afterthought. Perhaps through some of these pre-modern devices we can regain some of the character of the city.

1. Legg, Stephen. Spaces of Colonialism: Delhi’s Urban Governmentalities.

2. Hunt, Tristram. Cities of Empire: The British Colonies and the Creation of the Urban World.

Form + Function – Jantar Mantar

01.2016 - 03.2016

The Jantar Mantar complexes in New Delhi and Jaipur built by Maharaja Jai Singh II of Jaipur in the first half of the 18th century take the traditional astronomical measuring tools and enlarge them to increase precision; the larger sundial in Jaipur can indicate the time to an accuracy of seconds. Each instrument is built precisely for their geographic latitude and longitude which determines the slopes and geometrical configurations.

The large scale has required a spatialization of these objects, creating an architecture of observation in which the program rather than the space contained is the sculpture itself. Instead of ornament we have metrics. Furthermore, it has complicated the notion of figure/ground; some of the instruments are twinned, such that each represents the void of the other.

These projects can be seen as early grumblings of modernism, where form IS function. Each structure is attuned to a specific task of measurement, and a precursor to the later prismatic forms of Modernism in India. LeCorbusier’s Tower of Shadows at the capitol complex in Chandigarh follows a similar vein of research. Here the angle of the sun throughout the year is examined and specific shades are created to keep the interior space always in the shade. This pavilion serves as a prototype proof of concept for all the other projects to ensure that the interior spaces can remain cool.

Impressions – Delhi

01.2016 - 03.2016