12.2015 - 01.2016

In his essay Perspective as Symbolic Form Erwin Panofsky outlines the evolution of pictorial space from the isolated masses of classical antiquity, to the rationalization of matter through modern linear perspective during the Renaissance, and towards the possible erosion of this visual construct moving toward the present. In essence, linear perspective (both as a technique and as an aesthetic model) provided a total system for understanding space and objects in relation to one another, and thus carved out a realm for the human viewer to understand their consciousness in relation to the three-dimensional space described.

The ancient Near East, classical antiquity, the Middle Ages and indeed any archaizing art (for example Botticelli) all more or less completely rejected perspective, for it seemed to introduce an individualistic and accidental factor into an extra- or supersubjective world. – Erwin Panofsky [1]

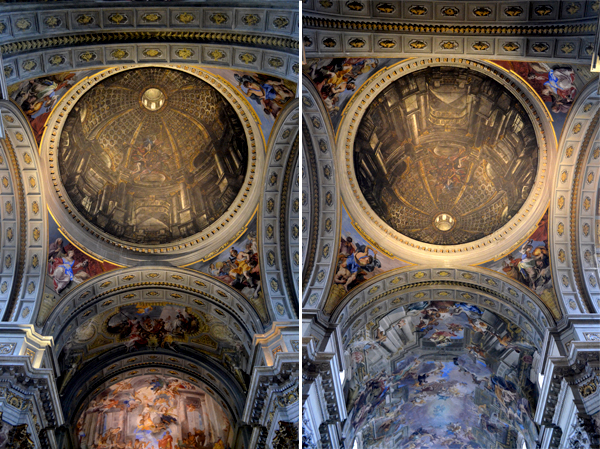

In Rome there abound examples of perspective being deployed in order to enhance, enlarge, or adjust space via trompe l’oeil in Renaissance and Baroque architecture. (This is not a reference to the abundance of examples where a fantastical view, such as upwards to heaven, which is so often painted across the ceiling of a great church.) The goal is to create the perception of actual, physical and occupiable space beyond. The examples vary widely: The facade of Palazzo Barberini (Maderno/Bernini/Borromini), and the niches at the landings of Bernini’s stair in the same building, both places where the effect is subtle and finding the proper viewing location for one alcove breaks the illusion of all other other instances. The false dome of Sant’Ignazio which extends space upward, or Andrea Pozzo’s painting for Saint Ignacio’s corridor at the Gesu which enlarges and corrects the irregular end geometry of the space. Most ingeniously, Bernini’s corridor at the Palazzo Spada which actually creates a three-dimensional space that is much longer than it appears by “vanishing” geometrically.

I believe that the largest Buildings of the Exposition, which will remain, must together constitute an immense Forum. Imagine standing in the midst of the Roman Forum, among the piazzas, colonnades, landscapes, arches, etc., and viewing in the distance to the left the Coliseum, and in the distance to the right the Campidoglio. An analogous vision, though modern, very modern. – Marcello Piacentini, 1937 [2]

Palazzo Barberini

Side aisles in Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano

The “dome” in Chiesa di Sant’Ignazio from directly below

The “dome” right-side-up and up-side-down

Palazzo Borghese

Palazzo Spada

The vestibule to the Museo Pio Clementino at the Vatican Museums

It is true that the image of EUR bears formal correlation to Francesco di Giorgio Martini’s Architectural Veduta [3] or the Ideal City paintings. But in these examples space seems to be in balance with the buildings, and even bounded by it. Instead, if we can understand E42 to be both a return to Roman ideals of planning and a trajectory towards the future, perhaps the better atmospheric or psychic reference would be Giorgio de Chirico.

De Chirico’s metaphysical space of isolated objects, harking back to the Classical idea of space portrays buildings as artifacts, objects floating without relation to one another or understanding of diminishing lines. De Chirico’s paintings with their fragmented planes allow the viewer to see all that is required to grasp a building. This attitude negates the individual perception of space for a more top-down hierarchical view. His imagery is clearly in vibration with both classical architecture and the “stripped classicism[4]” that epitomizes many Fascist buildings particularly by Marcello Piacentini. Even the broad barren open spaces can be a tactic to make each building more of an object, only compositionally related to the others, but otherwise in isolation.

Piazza San Pietro by Bernini which places primacy on the two foci of the elipse | Museo della Civiltà Romana by Aschieri, Bernardini, Pascoletti & Peressutti whose columns are ordered orthogonally

Palazzo Civiltà Italiana

Perspective subjects the artistic phenomenon to stable and even mathematically exact rules, but on the other hand, makes that phenomenon contingent upon human beings, indeed upon the individual: for these rules refer to the psychological and physical conditions of the visual impression, and the way they take effect is determined by the freely chosen position of a subjective “point of view.” Thus the history of perspective may be understood with equal justice as a triumph of the distancing and objectifying sense of the real, and as a triumph of the distance-denying human struggle for control; it is as much a consolidation and systematization of the external world, as an extension of the domain of the self. – Erwin Panofsky [5]

While the fronts of many Baroque churches are astounding, often they are sited such that it is virtually impossible to view them in pure elevation, thus it is just as much the tension in the surface, of columns emerging or receding to become pilasters and that three dimensionality that is expressed. The buildings at EUR are always to be viewed frontally or as a series of thresholds along a grand roadway. They lack the texture of their Renaissance predecessors, combining the imagery of Roman geometry and modern simplified forms lacking decoration, with only symbolic inscriptions and monumental bas reliefs. They can be understood through orthographic projections (plans, sections, elevations) and there is a didactic quality to them, for example at the Palazzo Civiltà Italiana with the arch as a sign, repeated over and over again. Even the glass is recessed to allow the mass to read more sculpturally without obvious reflections. Indeed this gives the project the almost skeletal appearance of a found monument; naturally this building is referred to as the “Square Colosseum.” Rather than the particularity of perspective, these projects are an expression of the collective.

1. Panofsky, Erwin. Perspective as Symbolic Form. 71.

2. Una Nuova Roma. L’Eur e il Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana. http://www.eurspa.it/area-stampa/news/al-colosseo-quadrato-una-mostra-racconta-l-eur

3. Innamorati, Francesco and Enrico Valeriani. EUR: Quartiere di architetture “tradizioni nell’innovazione”.

4. Ghirardo, Diane Yvonne. Italy: Modern Architectures in History.

5. Panofsky, Erwin. Perspective as Symbolic Form. 67-8.