06.2016

While the capital city is a completely immersive 3D experience ideally representing the aspirations and values of its nation, it is also an image for media dissemination with a handful of singular places and objects representing the whole population. The expo exists at an intermediate level as a curated experience of highlights, showcasing the host city, as well as the representative guest countries in a series of short and curated clips.

From the Great Exhibition in London and the purpose-built Crystal Palace to next year’s Expo 2017 in Astana, the apparatus for framing the discussion of innovations (technological, artistic, social, etc.) through an exhibition has become more regulated and repetitive. Both these examples are structured within the framework of a unified campus showcasing the technological capacity of the host nation. The Astana Expo at the least intends to present alternative energies (in a country whose economy is largely dependent on petroleum) and to integrate the site into the city’s growth for the future.

Above: Sverre Fehn’s iconic Nordic Pavilion for

Construction on Astana’s Expo 2017 | The Chinese pavilion from Shanghai Expo 2010 is now the China Art Palace

Other events such as the recent expos in Hanover (2000) and Shanghai (2010) have used architecture constructed by invited countries as both a frame for, and as part of their presentation. Only some of the buildings have survived after the expos closed, though the most successful may nevertheless enter the architectural canon via published images.

Germany creates “Open Doors” | Canada’s exhibit outside their pavilion

The epitome of the architecture exhibition is the Venice Biennale. Because it is a repeated event many countries have permanent pavilions in the Giardini which represent a national character or ideal at a very specific time. A few of the pavilions in the Giardini have taken on a more iconic status than any of the exhibits ever will. Alvar Aalto’s “temporary” pavilion would be just as appropriate on the shore of a Finnish lake. The Nordic Pavilion by Sverre Fehn has entered the canon, though the ingenuity of his trees puncturing the roof has been hidden by this year’s installation. Venezuela’s pavilion was designed by local master Carlo Scarpa. The German exhibit on their immigration policy created openings into its walls which must be blocked later due to the landmark status of their pavilion, and the Serbian Pavilion still has “Jugoslavia” in relief over its entrance.

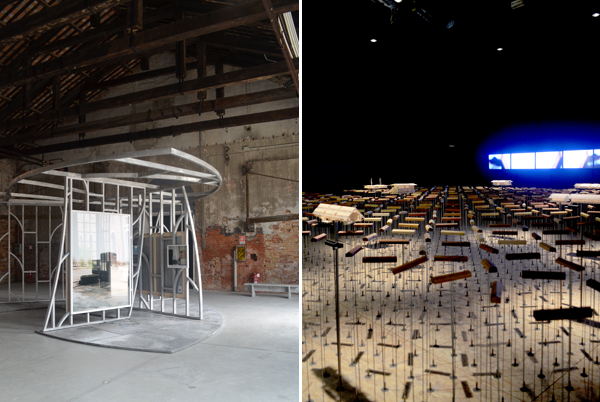

The exhibitions are just as varied, notionally related to the year’s chosen theme. Countries which are represented in the Arsenale have the opportunity to create an immersive exhibit in a black-box setting rather than interacting with the specifics of a purpose-built pavilion. The connection between the curator’s theme (this year Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena chose the title “Reporting from the Front”) and each installation can be tenuous, although hewing closely can result in a golden lion. Again there is a spectrum of approaches, from the commission of specific work or research addressing an aspect of the theme, to most mundanely a collection of national projects.

Related to the current global conditions, Germany, Finland and the Netherlands addressed the issues surrounding refugees in different contexts. Of particular note this year was a temporary pavilion commissioned by the curator in the Giardini revealing the conditions of the Sahrawi’s, the majority of whom do not live within the borders of their country, but in semi-permanent refugee camps in Algeria. The pavilion addressed not only the quotidien functions which make a camp into a settlement, but the specific programs which one might also see in a capital city including various ministries of justice, culture and defense.

Bahrain and Thailand in the Arsenale